- Instrument

- March 18, 2021

The Northumbrian smallpipes (also known as the Northumbrian pipes) are bellows-blown bagpipes from North East England, where they have been an important factor in the local musical culture for more than 250 years.

Northumbrian Pipes Performers

The family of the Duke of Northumberland have had an official piper for over 250 years. The Northumbrian Pipers’ Society was founded in 1928, to encourage the playing of the instrument and its music; Although there were so few players at times during the last century that some feared the tradition would die out, there are many players and makers of the instrument nowadays, and the Society has played a large role in this revival. In more recent times the Mayor of Gateshead and the Lord Mayor of Newcastle have both established a tradition of appointing official Northumbrian pipers.

In a survey of the bagpipes in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University, the organologist Anthony Baines wrote: “It is perhaps the most civilized of the bagpipes, making no attempt to go further than the traditional bagpipe music of melody over drone, but refining this music to the last degree.”

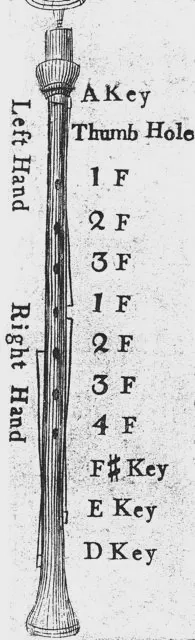

The instrument consists of one chanter (generally with keys) and usually four drones. The cylindrically bored chanter has a number of metal keys, most commonly seven, but chanters with a range of over two octaves can be made which require seventeen or more keys, all played with either the right hand thumb or left little finger. There is no overblowing employed to get this two octave range, so the keys are therefore necessary, together with the length of the chanter, for obtaining the two octaves.

The Northumbrian smallpipes’ chanter having a completely closed end, combined with the unusually tight fingering style (each note is played by lifting only one finger or opening one key) means that traditional Northumbrian piping is staccato in style. Because the bores are so narrow, (typically about 4.3 millimetres for the chanter), the sound is far quieter than most other bagpipes.

A detailed account of the construction of Northumbrian smallpipes written by William Alfred Cocks and Jim F. Bryan was published in 1967 by the Northumbrian Pipers’ Society; it was very influential in promoting a revival of pipemaking from that time. This is now out of print, however. Another description, by Mike Nelson, is currently available. Nelson’s designs also include the “School Pipes”, G-sets with plastic components, made to be used in schools in Northumberland. These two accounts differ rather in their objectives, as Cocks and Bryan was based on descriptions of existing sets, notably by Robert Reid, Nelson being a description of his own design.

Repertoire

The earliest bagpipe tunes from Northumberland, or indeed from anywhere in the British Isles, are found in William Dixon’s manuscript from the 1730s. Some of these can be played on Border pipes or an open-ended smallpipe like the modern Scottish smallpipes, but about half the tunes have a single octave range and sound well on the single-octave, simple, keyless Northumbrian pipe chanter. These tunes are almost all extended variation sets on dance tunes in various rhythms – reels, jigs, compound triple-time tunes (now known as slip jigs), and triple-time hornpipes.

At the beginning of the 19th century the first collection specifically for Northumbrian smallpipes was published, John Peacock’s Favorite Collection. Peacock was the last of the Newcastle Waits (musical watchmen), and probably the first smallpiper to play a keyed chanter. The collection contains a mixture of simple dance tunes, and extended variation sets. The variation sets, such as Cut and Dry Dolly are all for the single octave keyless chanter, but the dance tunes are often adaptations of fiddle tunes – many of these are Scottish, such as “Money Musk”.

A pupil of Peacock, Robert Bewick, the son of Thomas Bewick the engraver, left five manuscript notebooks of pipetunes; these, dated between 1832 and 1843, are from the earliest decades in which keyed chanters were common, and they give a good early picture of the repertoire of a piper at this stage in the modern instrument’s development. Roughly contemporary with this is Lionel Winship’s manuscript, dated 1833, which has been made available in facsimile on FARNE; it contains copies of the Peacock tunes, together with Scottish, Irish, and ballroom dance tunes. Both these sources include tunes in E minor, showing the d sharp key was available by this date.

As keyed chanters became more common, adaptations of fiddle music to be playable on smallpipes became more feasible, and common-time hornpipes such as those of the fiddler James Hill became a more significant part of the repertoire. The High Level is one. Many dance tunes in idioms similar to fiddle tunes have been composed by pipers specifically for their own instrument – The Barrington Hornpipe, by Thomas Todd, written in the late 19th century, is typical. Borrowing from other traditions and instruments has continued – in the early-to-mid 20th century, Billy Pigg, and Jack Armstrong (The Duke of Northumberland’s Piper) for instance, adapted many tunes from the Scottish and Irish pipe and fiddle repertoires to smallpipes, as well as composing tunes in various styles for the instrument.

Although many pipers now play predominantly dance tunes and some slow airs nowadays, extended variation sets have continued to form an important part of the repertoire. Tom Clough’s manuscripts contain many of these, some being variants of those in Peacock’s collection. Other variation sets were composed by Clough, such as those for Nae Guid Luck Aboot the Hoose which uses the extended range of a keyed chanter.

Playing style

The traditional style of playing on the instrument is to play each note slightly staccato. Each note is only sounded by lifting one finger or operating one key. The aim is to play each note as full length as possible, but still separate from the next – ‘The notes should come out like peas’. The chanter is closed, and thus briefly silent, between any two notes, and there is an audible transient ‘pop’ at the beginning and end of a note.

For decoration, it is common to play short grace notes preceding a melody note. Some pipers allow themselves to play these open-fingered rather than staccato, and Billy Pigg was able to get great expressive effects in this way – ‘You should be able to hear the bairns crying’. But ‘choyting’ (the complex open-fingered gracing after the manner of Highland piping) is generally frowned on, and Tom Clough made a point of avoiding open-fingered ornament altogether, considering open-fingering ‘a grievous error’. Several pipers play in highly close-fingered styles, Chris Ormston and Adrian Schofield among them; even among those such as Kathryn Tickell who use open fingering for expression, the close-fingered technique is the basis of their playing.